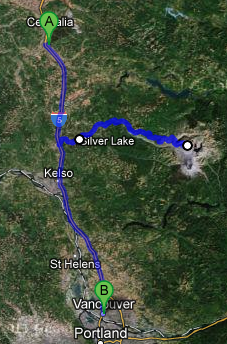

Woke up, grabbed breakfast from the free buffet, and spent some time updating yesterday’s blog with pictures (so, if you haven’t seen them yet, do so!). We headed out about 10:30 or so, down I-5 towards Castle Rock. In Castle Rock we grabbed some Subway to eat later (as it was only 11 o’clock) as the choice of restaurants on the road to Mount Saint Helens is nigh non-existent. The family almost forgot my sub and it was only the heroic efforts of the Subway staff that got it into my eager hands.

We headed east on route 504 about five miles before arriving at the Mount Saint Helens visitor center. We watched a fascinating fifteen minute or so movie about the eruption on May 18, 1980 as well as the aftermath. As this post progresses more and more details will be given, and I point anybody to Wikipedia for all the nitty gritty. Basically, though, in the two months prior to the eruption frequent earthquakes (numbering 10,000 before the eruption) occurred and a bulge on the north side of the mountain formed, growing by as much as five feet a day. On the day of the eruption a 5.1 magnitude quake occurred just below the bulge, leading the entire north face of the mountain to collapse into the river valley below in the largest landslide in recorded history. The magma that had been building that bulge, now relieved of all of the rock keeping it from exploding, shot out laterally in a very violent explosion that soon overtook the landslide at 300+ miles per hour and well over 300F. Later in the day the eruption finished with a more traditional vertical eruption that also sent out a series of pyroclastic flows that covered the peak. The peak went from being the sixth highest point in Washington at about 9600 feet to the eighty-seventh, having lost just over 1300 feet. Remarkably just 57 people perished, largely due to the efforts of the USGS to convince local authorities to close the mountain and keep it closed despite public pressure to re-open it.

Also in the visitor center were descriptions of volcanoes on other bodies in our solar system. Turns out Venus has the most, and Mars’ are massive as its crust does not move so, unlike Earth’s geologically short-lived ones, volcanoes can grow massive as they sit over the hotspot forever. A nice timeline of the eruption period and its aftermath, including the eruptions in 1982 and the 2004 – 2008 period of activity, was also there, complete with contemporary newspapers. Not only was Mount Saint Helens prominently featured but so was the Iran hostage crisis and that Bank of America and other banks had raised the prime interest rate to twenty percent! Now, our economy isn’t doing great, but at least we haven’t seen that (yet). I remember that period, and the strain that put on the finances of my parents. Twenty percent!

Also shown was that Mount Saint Helens’ ash discharge was actually pretty tiny compared to other historical volcanoes — including Mount Mazama, the very volcano that formed Crater Lake (which we’ll be visiting next week) 4,500 years ago. Mount Saint Helens’ impact was more immediate due to the unusual lateral eruption and the preceding landslide.

We headed back to the car (after seeing a two foot snake slithering across the entrance to the center) and ate our Subway, then continued along route 504 towards Johnston Observatory. Along the way we stopped at several viewpoints and enjoyed amazing views of the mountain as well as the Toutle River valley. Even now the Toutle River is one of the most heavily sedimented rivers in the world as it drains Mount Saint Helens’ blast zone. We also saw stands of Noble Fir that were packed together and so uniform that it looked very, very odd.

The weather was still quite overcast as it had been all morning, but bits of blue were starting to appear. Finally (after a climb to over 3,000 feet then a descent then another rise to just over 4,000 feet) arrived at the Johnston Observatory about five miles north of the volcano. It was named after David A. Johnston, a geologist who died at his post on the ridge and had been instrumental in convincing that the area be closed and remain closed. He saved countless lives (in the thousands) as a result. In addition the fact that it occurred early on a Sunday saved many lives as well — loggers only got Sunday off so 300 of them were at home rather than working. Property owner pressure had led to a convoy of fifty cars to enter the area the day before and another was scheduled for 10 o’clock on Sunday but the explosion happened before that rather than catching a couple of hundred property owners off guard.

At the observatory we watched two movies, on with a biological focus (kinda boring) and one with a geological focus (boom! yay!). At the end of each the screen lifted up and then the curtain behind it, revealing a full glass wall with the volcano’s crater looming across the entire expanse. Very, very cool.

Checked out the exhibits a bit, learning that Johnston’s last words were “Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!” (Vancouver being the location of the USGS office) and that the tremendous speeds of the landslide and blast (well over 300 mph). We stepped out onto the patio and, while taking some pictures, got sucked into a fantastic presentation by a ranger.

He described the blast in great detail, including information such as an area the size of Chicago was leveled in three minutes. The blast knocked down tons of trees (and you can tell how the blast traveled as the trees point to the direction of the blast) and then the arrival of the landslide scoured the blasted areas to bedrock and carried the trees downstream or into the lakes. Even today you can see the extents of the landslide as there are trees down all over the tops of the ridges but then they aren’t found at the bottom where the slide scoured the earth. Trees and debris hit Spirit Lake, causing the waves that shot water up to 800 feet along the lake’s sides, dragging down a load of logs into the lake. As a result the lake grew tremendously in size (as it was dammed) and dams along Coldwater and Castle Creeks led to two new lakes (that still exist today).

Mud and debris flowed down the rivers flowing out of the area, sweeping away over three hundred homes and many bridges. The Columbia river went from a channel depth of 40 feet to just over 16 feet. Immediately in the landslide area there was between 150 and 600 feet of debris on top of the original land as well as large clumps of the mountain called hummocks. Later in the day of the eruption pyroclastic flows sterilized the upper reaches of the mountain (still, to this day). Mudflows as a result of an eruption in 1982 helped dig up to 200 foot deep chasms in the landslide debris through which rivers run even today.

Even with all of this destruction, however, there was life. Along the north face of Johnston Ridge some trees that were buried under a snow bank survived. Some burrowing animals survived and in the process of their re-building dragged seeds to the service where they could take hold. Plants started to grow and elks helped greatly by entering the park and pooping, their poop containing and fertilizing many seeds.

Finally the guide told us the fascinating tale of a salamander that had juveniles that survived as they still had their gills and lived while the adults that had gotten lungs and had to go to the surface had died. Even after the eruption many of the salamanders would hit adulthood only to die when they surfaced from the lake they inhabited but had no shelter from predators, among other things. What happened was remarkable — prior to the eruption there was a small (< 10%) percentage of the population that would not ever grow lungs (aka, become adults) but were able to reproduce. They had an inherent advantage because they didn’t have to leave the underwater realm. After the volcano they continued to thrive and reproduce, such that over 90% of the population of these salamanders never grow up but can still reproduce. Nature is amazing.

The talk finished we headed up a small walkway with wonderful views. The clouds were really starting to retreat though the crater never became cloud-free. We returned to our car and went back to I-5 via route 504 and drove to Vancouver, WA about forty minutes away. Along the way we paralleled the Columbia River a bit which was cool — my first sighting of Oregon!

In Vancouver we checked in to our hotel and went to the Outback in the local mall. It was decent Outback food, something Addison had been really wanting since the trip began. Oddly the Outback was actually part of the mall (something we’d never seen) and was about 25% more than back in North Carolina. And no sweet tea, of course! Grrrrr!

After Outback we went into the mall and saw some really cute kitties in a pet store (I had no idea that those type of stores were still around). Went to a place called Tilt that claimed to have arcade and pinball games but instead was really, really lame — other than skeetball it was just claw games, DDR type stuff, racing cabinets, the like. Ugh. Finished up by getting a little icecream from Baskin & Robbin’s 31.

Returned to the hotel and went swimming / hot tubbing with Addison while Michelle and Genetta watched the opening ceremonies. Returned back to the room and started blogging.